What Does Research Say is the Best Way to Learn a Language?

Language learning is a topic close to my heart. Few things are more exciting than talking to someone in a language that was, until recently, incomprehensible to you. But as exhilarating as it is when you get it right, learning a language can also be full of frustration, misunderstandings and embarrassing mistakes.

Most of my knowledge of learning languages comes from first-hand experience. I had a bumpy time learning French during a year abroad while in college. Later, I had a better experience learning four different languages in a year while traveling with a friend.

Despite years of self-experimentation, I hadn’t looked into what careful research has to say about what works—and what doesn’t—in language learning. Recently, I decided to start to remedy that by reading a handful of books on the science of second language acquisition. The best was Patsy Lightbown and Nina Spada’s How Languages are Learned.

Evaluating Six Different Approaches to Language Learning

Written as a training guide for second language teachers, Lightbown and Spada’s book covers a broad swath of language acquisition research. I found the chapter summarizing six popular approaches and the evidence for and against them to be fascinating.

1. Accuracy first.

Translation was the classical approach to teaching languages. Students were given vocabulary lists and grammatical rules and expected to translate Latin or Greek texts. While this may have been useful for appreciating ancient literature, it is far removed from the communication goals of modern students learning French or Spanish.

Inspired by behaviorist psychology, the audio-lingual method sought to replace this text-based approach with a call-and-response format. In this newer approach, students produce correct sentences by strictly following an example from the teacher. By teaching the patterns correctly from the start, bad speaking habits wouldn’t develop.

Accuracy-first approaches have long been popular in the classroom. But among researchers, they fell out of favor as some of their underlying assumptions started to come into question:

- Most language use isn’t strictly imitative—we generate new sentences to express our meanings. The heavy repetition of audio-lingual methods might not reflect how we acquire real language.

- Languages (including second languages) emerge on a developmental timeline. Students appear to learn certain grammatical patterns in a fixed order, regardless of how they are taught. This suggests that avoiding all mistakes may actually be impossible.

- Classroom learning has a tricky relationship to spontaneous language use. The book mentions one study where students who were aggressively taught a particular pattern did use it more—but also made more mistakes in their other sentences!

Perhaps more than anything, however, Noam Chomsky’s devastating blow to B. F. Skinner’s behaviorist explanation of language encouraged researchers to look elsewhere for new approaches.

2. Input is all you need.

Stephen Krashen was one of the most strident critics of the “accuracy first” approach to language learning. His Input Hypothesis proposed that grammar drills and repetitive practice were, in addition to being inefficient, utterly ineffectual in producing real language acquisition.

Instead, Krashen’s theory holds that you only need comprehensible input to learn a language. Here, input refers to language you listen to or read for meaning, not to try to analyze its syntax. Thus a book, street sign or conversation you attend to in order to understand would be input. The sentences you copy from a textbook are not.

Input-based approaches have their appeal: drills aren’t particularly fun, speaking opportunities can be scarce and stressful, but books and audio recordings are available anywhere. One study even found that after two years in an input-based class, students performed as well (or better) than those in a more traditional class, including on measures of speaking—even though they never practiced it.

However, some studies refute some of the bolder claims of Krashen’s hypothesis. Research on French immersion students, who have huge amounts of language input, found that while they reach native levels of comprehension ability, they still make non-native mistakes in grammar while speaking, despite years of full-time immersion. Students do seem to benefit from explicit instruction on the forms and rules of a language.

3. Talking is everything.

Another theory of language learning is that students need interactive communication, not just input. Merrill Swain’s Output Hypothesis flipped Krashen’s Input Hypothesis around, arguing that the need to express more complex ideas could be a driver of language learning. Similarly, Michael Long’s Interaction Hypothesis argued that interactions, not just input, were essential for learning.

One advantage of interaction-based approaches is that dialog partners naturally adapt their level of communication to be understood by the student. In contrast, a book or audio recording is fixed, thus making it essential to find materials at just the right difficulty level.

Another advantage is that genuine communication allows students to hypothesize about how the language works and receive immediate feedback based on their success. In contrast, approaches that only emphasize input or drills don’t allow this experimentation.

However, purely interactive approaches, devoid of instruction in grammar, may make it harder to acquire correct speaking habits. Conversation partners typically don’t correct mistakes when their meaning is understood, and many students don’t make use of subtler forms of feedback when their incorrect utterances are repeated back to them correctly.

4. Learn a language on the side.

Time is a major constraint on language learning. Young children receive tens of thousands of hours of exposure in their native language. How can even a clever adult compete with only thirty minutes per week?

One solution to this dilemma is to combine language learning with other academic goals. In these programs, the language isn’t taught as a separate class but as the medium of instruction for other classes.

French immersion programs in Canada are one of the most successful examples of this. Beginning in kindergarten, anglophone students receive all their usual academic instruction in French, rather than English. By Grade 12, they not only have near-native abilities in French, but they have kept pace with their English classmates in learning the standard academic curriculum.

As an approach to language learning, the authors note that these programs can work great, but there are some drawbacks:

- Students can take several years to perform well academically in a new language, suggesting this approach might not work when immersion begins later or if students have insufficient time to adapt to the new language of instruction. The authors cite English immersion programs in Hong Kong that struggled owing to the academic pressures placed on students.

- As discussed previously, immersion programs may not produce native levels of speaking if students have insufficient opportunity for practice or not enough attention is paid to teaching the language itself.

5. Study in the proper sequence.

In the late 1980s, Manfred Pienemann and colleagues showed that the rules of a language cannot simply be learned in any order—second language learners, like children learning their mother tongue, acquired grammatical rules in a fixed order that did not change with instruction.

According to this view, some features of a language, such as vocabulary, can be taught at any time. Other features—like using the word “did” to turn a sentence into a question in English, e.g., “Where did you put it?”—proceed on a fixed developmental sequence.

This approach contradicts the first one—if some mistakes are due to developmental transitions that cannot be skipped over, incessantly focusing on correcting mistakes is counterproductive.

However, the authors argue that the proper lesson to draw from this research is not that grammar does not benefit from instruction, simply that it is best to do so in the order that matches how students naturally progress.

6. “Get it right in the end.”

Reviewing the previous approaches along with decades of accumulated research, Lightbown and Spada argue that we should avoid some of the excesses of past language learning fads.

- Unlike the audio-lingual approach, students should have a chance to use the language meaningfully from the beginning.

- However, rather than focusing on pure input, interaction or immersion approaches, most students will find some focus on the forms of a language helpful in achieving accurate levels of speech.

The authors review a number of studies showing that students dramatically improve on their performance with particular patterns, provided those patterns are explicitly taught and practiced. However, it is also clear that real language ability is unlikely to emerge without time spent genuinely communicating.

Reflecting on My Approach to Language Learning

It was interesting to read about these theories, and the heated debates they have provoked, in part because my language-learning approach doesn’t neatly fit into any of them.

My preferred method for learning a new language is going “no English” for a period of time, switching all or most communication over to the new language. This is probably closest to the interactionist paradigm, arguing that conversations, not just drills or input, are important for proficiency.

However, reflecting on my experiences, I can also see that the traditional staples of grammar practice, flashcards and corrective feedback were key. In every language I’ve learned, I’ve done these exercises.

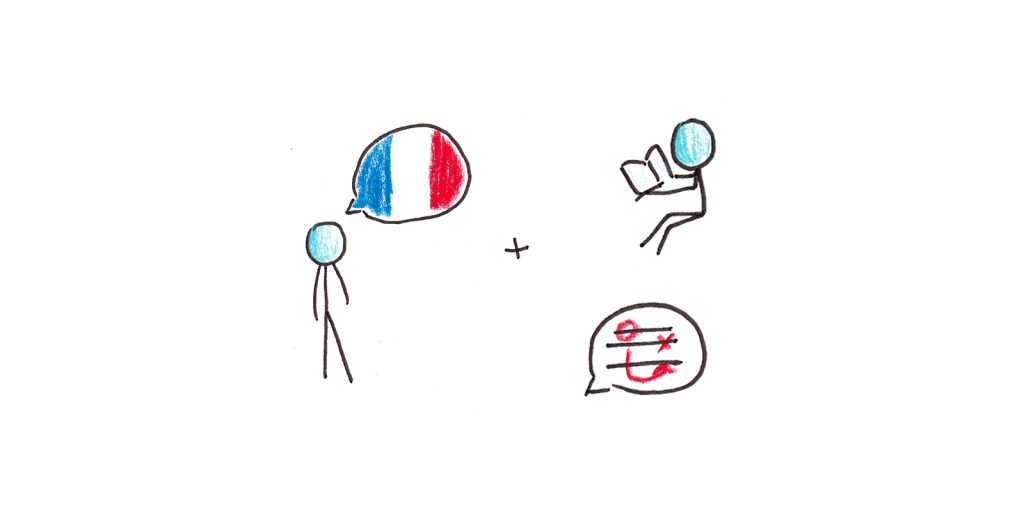

The mental model I have of my language learning is that more formal kinds of practice are often the best place to first learn about a new word or grammar pattern, but situations requiring genuine communication allow me to repeat those patterns in enough contexts so they become effortless and automatic. Only at higher levels of fluency did I find myself regularly learning new patterns just through interaction.

I might have previously underestimated how far people can get through reading and listening alone. I’m still not a convert to Krashen and his followers’ belief that speaking and instruction ought to be avoided. But, the fact that studies show students do seem to acquire speaking ability without much speaking practice seems important in situations where speaking is costly or impractical.

Language learning continues to fascinate (and occasionally frustrate) me, so I enjoyed reading Lightbown and Spada’s in-depth discussion of what science has discovered about it.

Link nội dung: https://thoitiet.pro/how-do-people-learn-languages-a1641.html